-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Fabian Renger*, Alfred Renger and Attila Czirfusz

Corresponding Author: Fabian Renger, Medical Care Centre, Dr Renger / Dr Becker, Heidenheim, Germany.

Received: April 04, 2024 ; Revised: April 08, 2024 ; Accepted: April 09, 2024 ; Available Online: April 11, 2024

Citation: Renger F, Renger A & Czirfusz A. (2024) Comparison of the Financing Structures between Outpatient and Public Health Institutes based on the Example of Medical Care Centers and Hospitals in Germany. J Nurs Midwifery Res, 3(1): 1-5.

Copyrights: ©2024 Renger F, Renger A & Czirfusz A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

Introduction: There are a variety of basic models for the financing of healthcare services. They affect how decisions are made as well as cash flow. The demand/need for healthcare services fluctuates in terms of volume over time. The aim of health insurance is to level out these fluctuations; this does, however, pose major problems (including negative risk selection and moral hazard).

Objectives: In Germany, the absolute expenditure for healthcare has increased steadily over recent years, but the relative percentage of gross domestic product has remained more or less consistent.

Methodology: In order to apply economic analyses effectively, costs and benefits must be incorporated into the investigations and comprehensively assessed. As a result, the advantages and disadvantages brought about by a project need to be considered not only from the perspectives of the individual decision-makers but also independently of whom they help and whom they disadvantage. This paper aims to solve the problem of comparability of healthcare facilities by means of comparative analyses and easily interpretable comparisons.

Results: The COVID-19 pandemic revealed structural problems in the financing of German hospitals and dramatically worsened their economic situation. A fictitious example of a planned MCC with two doctors from different disciplines can be used to depict the effects on the earnings situation in accordance with the provisions that are still in force.

Conclusions: The billing of an MCC’s medical services to the SHI-accredited doctors association (KV) is done on the basis of a SHI-accredited doctor ID number. This means that the MCC as an approved service provider is given an individual billing number-regardless of the number of freelance/employed doctors working there. The MCC is thus comparable to the previous multidisciplinary group practices.

Keywords: Economic analyses, Healthcare facilities, COVID-19 pandemic, Hospitals, Medical care centers, SHI-accredited doctors association

INTRODUCTION

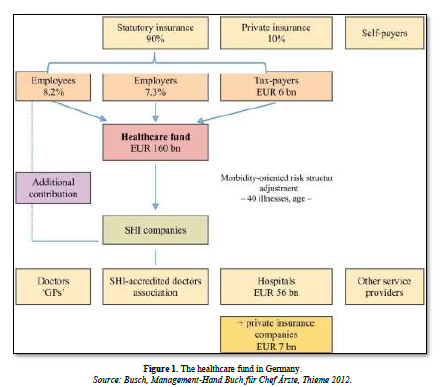

Since 1 January 2015, statutory health insurance (SHI) has had a uniform contribution rate across Germany of 14.6% of income subject to social security deductions-capped at an income of EUR 4,687.50/month or EUR 56,250/year (contribution ceiling, status 2020). All contributions are added to the healthcare funds, along with additional financing from tax revenue. The statutory health insurance (SHI) companies are given a uniform basic lump sum from these funds for each insured person, plus age-, gender- and risk-adjusted increases and reductions, to cover their standardized service expenses. Membership in a private health insurance (PHI) scheme is an option for the self-employed, civil servants and employees above an income threshold of EUR 5,212.50/month or EUR 62,550/year (annual earnings limit (JAEG), also mandatory insurance threshold, status 2020). Roughly 8.7% of the population have full private health insurance. PHI companies do not pay into the healthcare fund [1]. Figure 1 shows the structure of the healthcare fund.

To date, the healthcare industry has been predominantly influenced by statutory health insurance (SHI) and the other branches of social insurance, with roughly 90% of the population insuring themselves against the consequences of illness in this way. The mandatory contribution-financed SHI system thus enables lower earners with above-average risk structure to consume medical goods and services. The transfer payments of the health insurance companies support the market demand for healthcare services. For the economy, this has the advantage that high-quality human capital can be developed and preserved, which also stabilizes the economic and social order. Furthermore, creating opportunities for consumption also represents a key factor in economic growth. The aim of privatizing healthcare services is to use market control and economic incentives to reduce the growth in healthcare expenses, relieve companies of non-wage costs, provide doctors with greater freedom in treatment choices and give patients and insured persons greater responsibility and autonomy. As a result, patients are viewed more in the role of a rational consumer, able to realize their individual preferences on the basis of demand [2].

MEDICAL CARE CENTERS

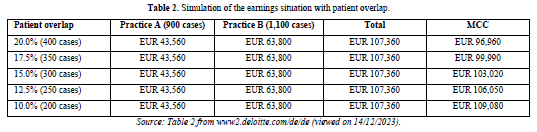

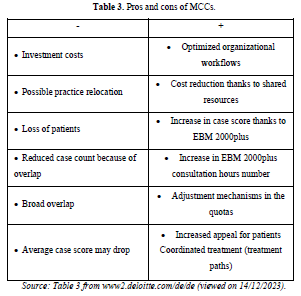

The overlap between patients treated jointly and services initiated for these patients has a considerable influence on the earnings situation of an MCC. Since the implementation of the German Health Insurance Modernization Act (GMG) on 1 January 2004, it has been possible to establish medical care centers on the basis of section 95 of Book V of the German Social Code (SGB V). A key feature is that MCCs are multidisciplinary healthcare institutions managed by doctors that are involved in SHI-accredited outpatient care with employed or freelance doctors by means of approval [3,4]. Many publications have addressed the requirements for establishment and approval, the configuration options, issues concerning SHI-accredited doctors and tax law, and the advantages and disadvantages. Less attention has thus far been paid to the question of whether an MCC pays off at all, given the specific billing stipulations agreed in the doctors’ fee schedule (EBM 2000plus). No general answer can be given to this question, as specific factors play a role in each individual case. Which specialist groups are involved in the MCC, what case count and what case score do the doctors provide, and how high is the percentage of patients that are treated jointly? There is no doubt that an MCC can be an attractive form of cross-disciplinary collaboration between doctors. However, establishing an MCC only makes sense if it is economically viable and if those involved are not worse off than they would be in a single-handed practice or in other forms of cooperation. But what organizational and billing-related changes apply in the case of an MCC? The billing of an MCC’s medical services to the SHI-accredited doctors association (KV) is done on the basis of a SHI-accredited doctor ID number. This means that the MCC as an approved service provider is given an individual billing number-regardless of the number of freelance/employed doctors.

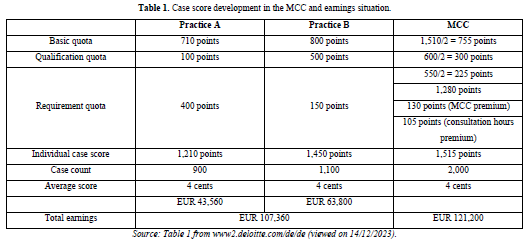

THE MCC’S CASE SCORE

In its 89th session, the evaluation committee agreed in its resolution on determining standard service volumes, with effect from 1 January 2005, that the case count of an MCC corresponds to the total of curative outpatient cases involving treatment (Behandlungsfall) of the doctors involved and the MCC’s case score is the arithmetic mean of the represented doctor groups. Accordingly, the curative outpatient care of one patient in the MCC constitutes one Behandlungsfall-regardless of how many doctors were involved in the treatment. This means that the consultation fee can only be billed once by the MCC for this patient. To compensate for this restriction, the fixed consultation services fee was increased by 15 points per represented doctor group for multidisciplinary group practices and MCCs. The minimum increase is 60 points, and the maximum increase 105 points-regardless of the number of doctors involved. According to the above-mentioned resolution, group practices and MCCs covering multiple doctor groups or sub-specializations receive an additional bonus score of 30 points for each doctor group represented, 130 points at a minimum and a maximum of 220 points. These billing provisions that apply for MCCs have been the subject of criticism. On the one hand, there is the problem of a lack of benchmarks for the new ‘specialist group’ MCC, and on the other, remedies, therapeutic aids and appliances and medicine prescriptions cannot be matched to the individual doctor. It is not yet clear to what extent the mandatory doctor-specific labelling in MCCs, which has been in force since 1 April 2005, has redressed this deficiency. An additional criticism is that an MCC can also suffer negative economic effects. The current billing provisions with the additional charges on the consultation fee and case score do not sufficiently consider the breadth and depth of an MCC’s services. A fictitious example of a planned MCC with two doctors from different disciplines can be used to depict the effects on the earnings situation in accordance with the provisions that are still in force. The following three tables depict the earnings situation for the two single-handed practices compared with an MCC in accordance with the applicable billing provisions (Tables 1 to 3).

Hospital situation

In the coming years, the economic situation of hospitals will remain tense regardless of the final structuring of the hospital reform. To enable hospital management to adapt to this, economic vulnerabilities must be addressed in a targeted manner. Successful hospital management is measured primarily on the basis of the following topics:

Current economic challenges in hospitals

The tense economic situation is the result of a long-term development in the German hospital market. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed structural problems in the financing of hospitals and dramatically worsened the economic situation: the majority of hospitals have not yet managed to recover from the effects of the pandemic. The sustained drop in inpatient cases (15% in 2022 compared with 2019) has caused enormous income losses for hospitals. Furthermore, costs are increasing massively in hospitals. While energy- and inflation-related material costs cannot be compensated for, there has also been a significant increase in recent years in the standard wages of doctors and nursing staff [5]. The situation is made worse by the ongoing nursing crisis. Almost all hospitals have been forced to close wards and beds because of a lack of nursing staff: to enable patient care, huge additional costs have to be incurred for temporary workers that can only partially be refinanced via the nursing budget. There have also been changes to the legal framework governing nursing, with the expansion of the nursing staff regulation 2.0, which calls for reporting on the deployment of nursing staff on wards. Relief wage agreements have also been introduced in certain federal states that use staff-patient ratios for specific wards and shifts as the basis for assessment [6]. Many clinics currently lack an overview of their deployment of nursing staff. The expansion of the framework conditions poses considerable problems for many hospitals. Overall, as a result of the current tense economic situation, only 20% of hospitals generated profit in 2022 and only 6% rated the current economic situation as good [6].

Changes in hospital financing

The upcoming changes to hospital financing are a response to the current economic challenges in Germany’s hospital landscape. The adoption of the hospital reform with its capacity financing will establish a new form of revenue distribution for hospitals. In addition, the volume of revenue has been expanded and now includes premiums to counter the chronic underfunding in certain areas (pediatrics, obstetrics, emergency care, stroke units, special traumatology and intensive care) [6]. Furthermore, the publication of the new AOP catalogue (catalogue of outpatient surgical procedures) in 2023 showed that a significant portion of current inpatient treatment can potentially be provided on an outpatient basis. As a result, the introduction of hybrid DRGs (diagnosis-related groups) is being discussed, which would expand the range of outpatient services for hospitals. Even though the first round of negotiations regarding the structuring of outpatient treatment failed, it can be expected that a solution will be found in the foreseeable future [6].

Impact of the current hospital reform

The previous financing system sets the wrong incentives by purely rewarding the number of cases and now seems out of date given the nationwide drop in case numbers, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic.

CONCLUSIONS

The billing of an MCC’s medical services to the SHI-accredited doctors association (KV) is done on the basis of a SHI-accredited doctor ID number. This means that the MCC as an approved service provider is given an individual billing number – regardless of the number of freelance/employed doctors. The MCC is thus comparable to the previous multidisciplinary group practices. The hospital reform is intended to counter the current DRG problems and, according to Federal Minister of Health Professor Lauterbach, save a large number of hospitals from bankruptcy. On 10 July 2023, the federal government and regional states agreed to a benchmark paper on hospital reform. The Hospital Reform Act will come into force on 1 January 2024. Following a convergence phase, the first capacity financing payments can be expected in 2026.

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :